“It was given to Abba Anthony to see a doctor in Alexandria who was simply and humbly doing what God had given him to do. His inner being stood in the presence of the Lord as he worked and prayed. According to the literature of the desert, this is the goal of our life in this world as it is set out for all Christians..."

― Elisabeth Behr-Sigel, The Place of the Heart: An Introduction to Orthodox Spirituality, emphasis added

The Orthodox tradition of the veneration of saints is one that many of us raised within the church take for granted, while often posing a stumbling block for converts from Protestant or non-Christian backgrounds. Among the many reasons I appreciate the practice is because the saints show us how unique holy lives can look.

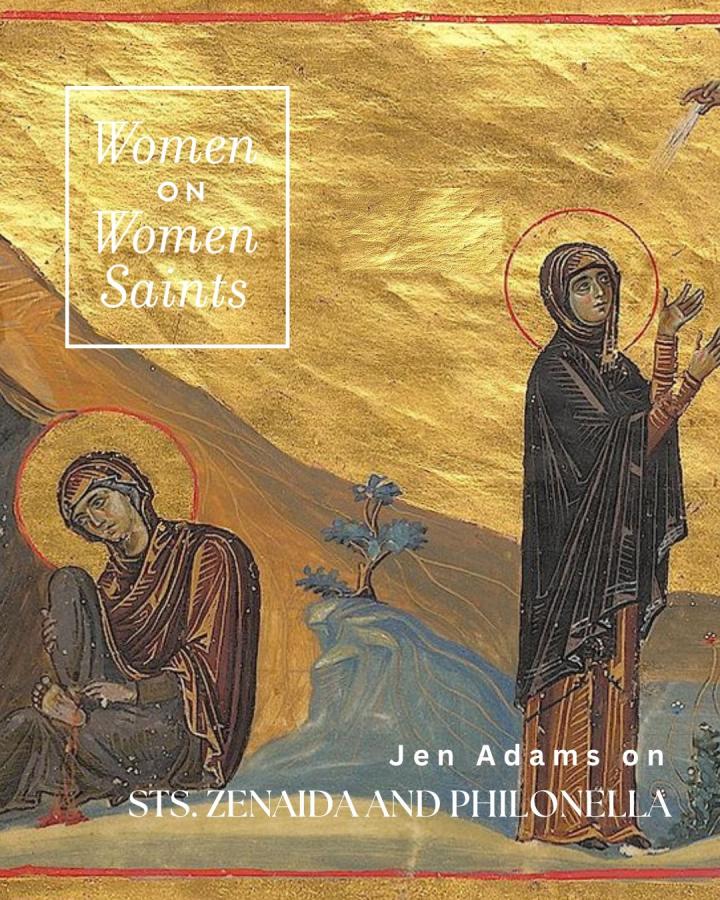

Two saints with whom I feel a personal connection are the sisters Sts. Zenaida and Philonella of Tarsus. We don’t have a lot of information about the sisters' lives, at least not in English, but the basics we do have paint an extraordinary picture. They were wealthy Jewish women who lived and chose to follow Christ in the first century after the resurrection. They studied medicine formally in Tarsus, a pursuit nearly unheard of for women of the time. After finishing their studies, they moved to the mountains of Thessaly where they opened a small clinic. Here the two set out to do the work that made them the first to earn the title of “Holy Unmercenaries”, since they treated all who came to them without expectation of payment. Their mountain-side clinic was located near a spring renowned among the pagans for its magical healing properties. Zenaida was interested in the medical care of children and those with mental illness while Philonella developed an investigative approach similar to what we would today call the scientific method. Zenaida also gained a reputation as a great spiritual teacher, of women and men alike. Four of her male students went on to found a monastery not far from the clinic.

These Holy Unmercenaries are so meaningful to me, first, because they were women who pursued their genuine interests and gifts, although that meant going against cultural norms and expectations. We don’t know how their family reacted, what kind of advice they were given from the other women in their lives, or how they were treated by their fellow students. We can observe that God was with them in their studies and labors, even though it wasn’t typical “women’s work” of the time.

Which brings me to the work itself. They were physicians. They treated the sick and suffering, not using magic or even miracles, but through their study and reasoned investigation of ailments and remedies. In this way, Sts. Zenaida and Philonella, and indeed every physician and healthcare worker since, have served as icons of Christ in a very specific ministry- that of healing. Often within Orthodox circles, we approach illness and suffering with the view that it is through this suffering that we can draw closer or become more like Christ Himself. While not untrue, we often neglect that when approached by the sick in his brief earthly ministry, Christ did not tell them how to view or experience their illness, but physically healed them. The woman with the issue of blood, the blind man, the leper, St. Peter’s mother-in-law, the paralytic lowered through the ceiling, the bodily deaths of Jairus and the centurion's daughter- in all these encounters, Christ healed the person before Him. Those with the call to heal today do so with the understanding that people have the freedom to interpret and respond to both suffering and health however they choose. As a healthcare worker, their lives also raise questions that I still grapple with. What does it mean to be Unmercenary today? Do I see an Icon of Christ in every person I encounter or just another colleague or patient? What does it mean to counsel on health or ease suffering when human life will end regardless, my own included?

Sts. Zenaida and Philonella lived out their faith in a manner that identified them as holy and wise people. Men and women alike sought their counsel and counted themselves their spiritual children. Within the past few centuries, the vast majority (but not all) of Saints recognized have been male monastics and male clergy. Holiness, that is a life of love- for God and the person before you- is not so narrowly confined, and saints are saints whether we recognize them as such or not. We, the women and men of the Orthodox tradition, lose so much when we fail to see holiness in all its diverse manifestations. The sisters served in a way contrary to how women of their time “should” and yet did so in a way that brought life, both physical and spiritual, to those around them. If we cannot see among women the same diversity of strengths and gifts that we acknowledge in men, we not only fall short of love of neighbor, but we open the door to shallow and foreign theologies.

Roughly two thousand years ago, two women were faithful to Christ and to the work placed before them. We can still feel the ripples from their lives today. I hope that others can find in their story both encouragement and challenge, as I have. I likewise hope in my lifetime to see more Orthodox women emboldened to pursue the true work God has placed in their hearts. May we as the twenty-first century Church have the courage to see and name holiness in all forms- in our unmercenary healers, monastics, reverend deaconesses, liturgists and theologians, mothers and teachers, and classes of saints as yet unrevealed.

Jen Adams is an occupational therapist from Austin, TX. She currently is working in Boston, MA on a research team investigating novel models of rehab care.