I was born in Serbia during World War II. When I was Christened in the small Russian Orthodox church outside of Belgrade, my Grandfather stood as my Godfather and my Aunt Anna as my “stand-in” Godmother. An old silver cross of my Grandfather’s was my baptismal cross, and apparently I howled loudly after the dunking. That was my introduction to Orthodoxy as a tiny newborn. Throughout the war, family prayer and Russian Orthodox family prayers sung aloud, morning and evening was a daily factor in my growing awareness. Every family member sang in the church and Grandfather was the choir director. I was supposed to be named Mary but for some reason that did not happen. Instead, I was named Tatiana in honor of my father’s aunt Tatiana Lvovna Tolstaya Sukhatina who lived in Rome and to whom my father was always close via correspondence.

By the grace of God, and the numerous prayers our family sent up to heaven on a daily basis, we got through the war and ended up in France to be met by my father’s family, anxiously waiting for our appearance.

I later learned that my Church- registered Godmother was Babushka Lina, my father’s mother, although I didn’t meet her until I was already 3 years old, after the war. Babushka Lina (Alexandra Vladimirovna Glebova Tolstaya) lived in Paris throughout the war and for a long time, my parents had lost contact with her because of the difficulty with wartime mail. When I did meet her, I was enveloped in her loving warmth and kindness, and from then on, she had a profound influence on my life, until her death in 1967 in Nyack, NY.

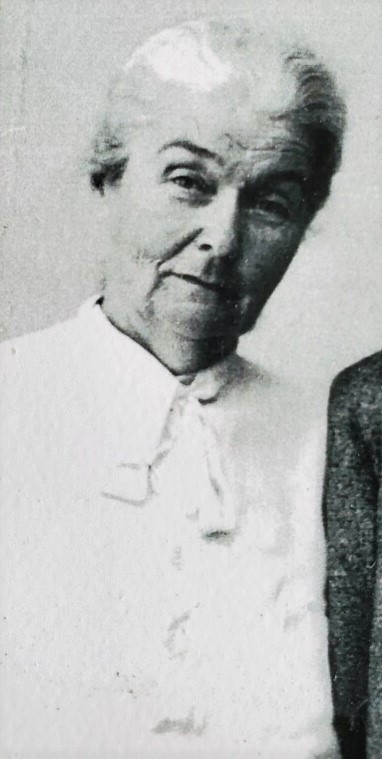

She was a tall straight-backed woman with white hair combed straight back and twisted into a roll at the back of her head. She never learned to keep house and my father’s twin sister Sasha, lived with her and took care of things. “Babu,” as my sister later named Babushka Lina, was born into very wealthy Russian nobility (Glebov on her father’s side, and Troubetzkoy on her mother’s side). Their homes still exist as museum estates around Moscow. Consequently, her take on daily life was different from most of the Russian immigration who surrounded her. Having fled revolutionary Russia, and losing everything, she maintained her dignity and raised her large family of 7 children, passing on her intelligence and her education, if not her practicality. She spoke several languages fluently and knew literature (Russian, French, English and German) backwards and forward. She had no sense of practicality at all and her culinary fame did not extend beyond making ground meat cutlets. However, she also knew art and was herself a fine artist although we her grandchildren had to draw the vases for her beautiful bouquets of flowers because she despaired of making them the right shape. She embroidered beautiful pictures copied from postcard reproductions of museum pieces. However, her first cousin who lived in Manhattan, and who earned a good living embroidering magnificent lingeree, sweaters, and evening wear, sniffed that “Lina has no sense of proper embroidery stitches.” I learned that Babu would regularly take the bus from Nyack to head for the Met Museum, to the Opera, to listen to professors discussing fine points of literature and participate in discussions on Russian history. From the time I was 4, she took over important parts of my education. She taught me to read and write Russian, but we also read aloud French books and English books and discussed them in detail. She gave me my first water colors, and I often sat with her drawing while she painted her own pictures. She took me to my first opera (Tales of Hoffman) and to the Metropolitan Museum.

But what does all that have to do with being a Godmother? It was more about who she was, and how she saw people and the world, rather than biblical or theological teaching. That was left To Fr. Seraphim Slobodskoy, our parish priest, and later discussions with my mother who enjoyed deep theological concepts and questions.

Babu’s personality was straight as an arrow, she expected truth and kindness. Although sometimes her upper-class prejudice showed through in a sniff at somebody’s vulgarity or crudeness, she never was openly rude or unkind to people, and would be generous to a fault in sharing what she had although it wasn’t much. She never complained. Never.

I did not find out that my grandfather had been unfaithful to her and abandoned her and her children in Paris for another woman, until I was an adult with children of my own. She never criticized him to anyone. Whatever she suffered, she suffered privately. Apparently, when he finally returned to her, she paced back and forth in front of him and finally stopped, stared at him and burst out, “You are such a fool!” And that was the end of it. When he became ill, she nursed him devotedly till his death. In the meantime, she coped with life such as it was, creating beauty as she could. All her children and grandchildren received her attention and her education and the example of her moral strength and fortitude. She was always sensitive to children.

Growing up in America in a Russian ghetto, I was often unsure of who I was. Was I Russian? Was I American? Where did I fit in? My parents had issues of their own trying to create a new life out of nothing. But Babu was always there to share something interesting in books or pictures, or poems, of which she knew very many by heart. And one very rare time, I was coming out of church, crossing the street to get in the car with her, she gave me a piercing stare. She took me by the chin, and chuckling said, “I was watching you across the street and I’m glad to say you have a very ‘sturdy’ look. I think you will be all right. You’re a ‘definite’ person.” I was taken aback because she never made personal comments like that. But I’ve treasured that statement because it was a very rare occasion of a positive personal feedback that gave me great reassurance.

And she had a very funny sense of humor. Her eyes had a slight Mongolian tilt to them (she claimed it came from some Tatar ancestors) and when she laughed they would totally disappear as she would fall apart in a high chuckling giggle. She appreciated funny things in literature and in people or situations, but she didn’t understand jokes, and was generally socially very shy.

Every Pascha she would prepare for confession especially lengthily. She always kept all the fasts. But before Pascha, during Holy Week, she was particularly strict and did not eat fish or oil and prepared for this confession with prayer, holy reading and silence. I still remember her little prayer book with the names of people to pray for. It was very long and she prayed for these people daily:for the living and for the dead. Sadly that list was especially long as she had lost so many family members and friends in the Revolution and the Wars.

The preparation for the most important communion at Pascha was called “gaveniye” and was how she was brought up. In Russia they had gone to a monastery to prepare and spent at least a week if not more in this special preparation. She had had a special elder who led her spiritually and during this preparation he would speak to her at length and guide her choices and correct her attitudes. As an immigrant, there wasn’t much opulence in any case, but fasting was taken seriously. She also told me about how Moscow erupted in Church Bells ringing at Midnight at Pascha. How the first toll was a deep bass gonging of the biggest bell in Moscow and then it was picked up by all the other churches in a synchrony of joyful sound. She said there was nothing more joyful than the whole city, the whole country rejoicing at Pascha. Growing up in a small town in America with Russia more of a fairy tale than a reality, these stories left a big impact on me. As did her love toward the experiences of her youth.

Although she had married Leo Tolstoy’s youngest son Michael, she never followed the Tolstoys’ religious attitudes. She was Orthodox to her bone, and held her faith very dear. The only things she ever told me about that sad family question, was that she was sorry for him (Leo), and for her mother-in-law Sophia. She felt that he was badly misguided in terms of Jesus Christ. She told me that in Russia many people in society had lost their way and that the Revolution happened as a punishment to turn people around and bring them back to God. “You know,” she told me, “He was such a brilliant writer; But not much of a philosopher. Maybe if he had to cope as we have had to in the immigration, he would have seen things more clearly.” I never forgot that opinion of hers. It was one of the rare times she shared any personal thoughts about her great father-in-law and his opinions about religion with me.

Every summer she would leave our family in Nyack and travel to the far north of Canada to live with her daughter Sophia’s family whose husband was a Forestry Engineer. They had three sons, whom I envied for their time with Babu. She had many amusing stories to tell about the lumberjack communities she shared with them. Once the bus she was traveling on got attacked by an enraged moose who destroyed the front end. They were stuck for hours until a new bus could be sent to rescue them on the forested dirt road. She was always a steady person, and didn’t like too much excitability. Even the moose didn’t upset her and she enjoyed the adventure and relished telling about it as a funny story.

She loved those summers as the nature reminded her of Russia. Her favorite pastime was walking for miles across the northern meadows collecting wild flowers. She returned with armfuls of them which she arranged and then portrayed in watercolors. My oldest cousin Serge, of course, had to draw the vase. When Aunt Sonia became widowed and moved to Nyack, Babu moved in with her and the boys, she had educated them, as she’d educated all of us, giving so much of herself, her stories, her literature and her love of beauty. I moved on in my life, married, had children of my own and saw much less of my Babu. She developed cancer of the breast in 1967. Shortly after, my first son John (Vania) was born and I stopped to see her on my way to church for his christening. She was weak, seated in her favorite soft chair. “Ahh” she said, “a little sunshine has come to visit!” And she held the baby on her lap, kissing his forehead and gave him a blessing. We sat a little, catching up. I gave her a hug noting her thin, bony shoulders, and I loved her so much. Little did I realize that was the last time I would see her alive.

As godmother, she left a huge impact on my life in terms of what it means to be a woman, to overcome immense difficulties, to lose every material possession and comfort, and to continue with faith, with dignity, with courage, with love and beauty. The final legacy she left me was in a dream after her death. Taken up with my new baby and coping with new responsibilities, I hadn’t visited her during her last illness. I felt so guilty about it and it bothered me very much. One night, I dreamt of her. She was young with long chestnut hair streaming down her back, she was striding through a meadow of wild flowers, her arms full of them. She had a wide smile and as she saw me, she paused and said, “Tanichka, don’t be sad. It is so beautiful here, there is only room for love and beauty!”

The photos above show Alexandra Vladimirovna Glebova Tolstaya at age 60, holding her first-born child, with most of her children, along with a photo of her goddaughter Tanya at age 5 which always stayed by her bedside, and one of her flower embroideries.

Tanya Penkrat holds a master's degree from St. Vladimir's Seminary and frequently blogs for Axia.