This weekend throughout the Eastern Orthodox world we remember St. Mary of Egypt. She is revered for her great life.

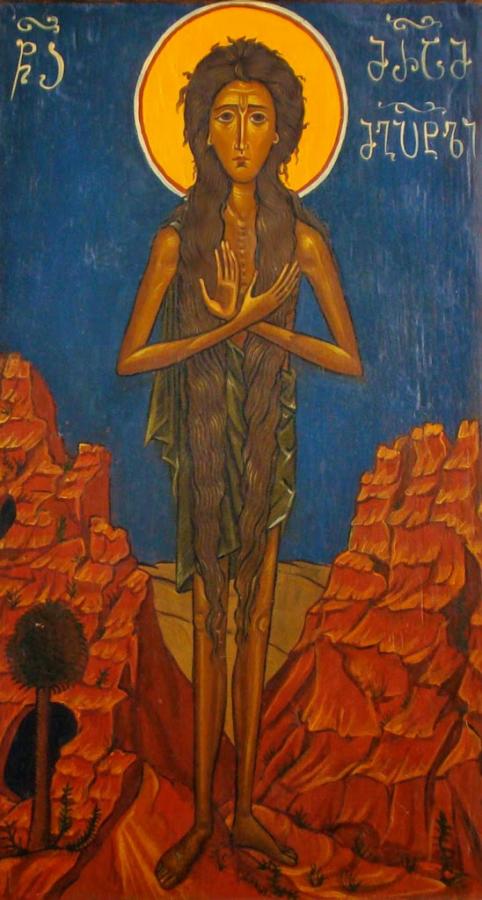

Here is an icon by my friend and priest Father Jerome Sanderson, one of the founders of the Fellowship of St. Moses the Black. There is the traditional reading by Sophronius and our prayers from the Triodion. In this post, I want to remember her and honor her in a way that puts a new light on her life and experience... one that respects her difficulties and phenomenal spiritual gifts. I am inspired by the writings of Dr. Pia Chaudhari, my many years working with young people, and discussions I’ve had with a wise and compassionate group of Orthodox scholars, clergy, and laypeople who’ve been studying scripture and theology together for several months over this last year.

These are St. Mary of Egypt’s words:

“When I was twelve years old, I renounced [my parent’s] love and went to Alexandria. I was like a fire of public debauch, often doing free of charge what gave me pleasure. For 17 years I lived by begging, often by spinning flax, but I had an insatiable desire and an irrepressible passion for lying in filth. This was life to me. Every kind of abuse of nature I regarded as life. That is how I lived.”

What if I met Mary then? Either just before she couldn’t enter the church, or just after. She is sitting in front of me: young, 29 years old.

My heart goes out to her. Her words echo...“debauchery “and “wantonness“ and “filth”.

I have been there with young people who have run away, living in the streets, unprotected from the perils and deadliness.

I’ve learned from workshops on trauma training not to ask or put the focus on “what did you do?” and not to ask, “Why did you do those things?” But rather ask: “What happened to you?”

I also learned something about me, about society, about our roles and responsibilities.

Acting out in this way, no matter the particulars, comes from situations of victimization that require a response. You can stay in the situation risking physical harm, depression and suicide--or you can escape into an unforgiving society.

Yes, she is a mess. She’s living a life of extreme deprivation and compulsion and self-destruction. But where is everyone else? What happened to her? Where is everyone else?

She does not give a reason for running away at 12. That’s really young,

Young people who came to me saying, “I can’t go home,” but often not saying why. Their feelings of powerlessness, confusion, danger, the sense that they brought it on themselves. It’s overpowering. They can feel alone, bullied, trapped into a destiny of slavery and servitude. We have young women, teenagers, forced into marriages with older men who keep their wives isolated, dependent, trapped in a world with no resources of their own. My grandmother was 14 years old when her family, who came from the West Indies, forced her into marriage with her second cousin—-whom she barely knew. She barely knew who she was herself. She ran away after my mother was born, leaving the infant girl with her parents. She lived on her own then, but stayed in touch with her family. We never knew how damaged she was by the situation, how the experience haunted her until a close relative became pregnant at 15. My grandmother immediately surrounded her with love, took her into her home, while the rest of the family dealt with the so-called disgrace, an actual fall from grace. She told the relative! “I was taken advantage of too.”

Quite a few of the women saints were running away from enforced marriages...

The runaways feel shame They may feel that what happened to them was the way things were meant to be. They deserved it. Maybe something about them elicited the hurt, the abuse and their families will not believe them or will shun them. Maybe the families are indebted to the abusers somehow. Or maybe the young people are attracted to the wrong people, dress out of their assigned gender roles, feel that they are in the wrong body and need to transition. And they are young. The people who are supposed to love and protect them are hurting them.

I learned to let them talk if they can. Show compassion and empathy, but first let them talk as they can. And we need to find them safety and support. Toothbrush, bed, shower. Then they can begin to tell their stories, to confess if they need to. But many have no one to turn to.

This is not unique. Tragically it’s not even unusual.

And Mary blames herself.

I am struck, then as now, by how blame falls on the individual sinner without regard to societal patterns and structures that allow this situation to fester--then and now. A fire of public debauchery means people saw her and knew what was happening to her and to other young people--then and now. They were living in filth, vulnerable to drugs, violence, self-harm--then and now. And she talks about all the men ... she was a child, a very young woman. Then and now. Vulnerable to predators--then and now.

Collapse the time here. In today’s Gospel reading, the woman, the “harlot” is bathing Jesus’s feet with precious oil, drying them with her tears. The people at the dinner knew one thing about her --she slept with men—- and they hated her for it. She was drawn to Jesus because she saw in him someone of great holiness and compassion.

Then there’s the story of the woman caught in adultery. In the full story she had been followed and pursued. Jesus interrupted the execution. He forced the stone throwers, the men, to face their own sins, and then released the woman, saying, “Go, sin no more.“ Her treatment, her on-going support, comes after Jesus protects her, shows mercy, shows love.

Mary did what she did to survive. She begged, she worked spinning linen, she slept around. She developed a bravado, a shell of invincibility. She saw the perverse use of her body as a sign of success, It showed she was desired. She could control that. Until she tried to enter that church. And all that fell away.

It fell away at the church doors with her encounter with the Theotokos.

As Pia Chaudhari writes, Mary of Egypt’s story is not just as an icon of repentance in the way we often hear that word, but of “love breaking through deeply patterned behavior and holding open the door to a different way, one she would have to fight body and soul, tooth and nail, to hold on to. Her experiences of God must have been very, very strong to effect such a radical metanoia and then sustain her for the ensuing battle with all the demons and complexes which would still be there in her psyche. The fight was on.”

Mary was baptized and crossed the River Jordan. She put on the armor of Christ, the clothes of Christ.

We wouldn’t encourage the anorexia and self-harm today she inflicted on herself then. But the role of the Theotokos as her sponsor is familiar and powerful now.

She says whenever she was tempted, “I returned to the icon of the Mother of God which had received me and to her I cried in prayer. I implored her to chase away the thoughts to which my miserable soul was succumbing. And after weeping for long and beating my breast I used to see light at last which seemed to shine on me from everywhere. And after the violent storm, lasting calm descended.” It fits the narrative of arduous discipleship, the endurance it takes to successfully climb the ladder of divine ascent to theosis, finding the light of God.

But there is more. I see the story of a child in trouble. I feel the need to respond as Jesus did with compassion and protection. We are the ones to attend to the runaways, the cast-outs, the lost people in society. We see Mary’s miraculous story but we must look beyond her and include other people in our duty of care, our duty to help facilitate the daily needs of food, shelter and safety, acceptance and community, that can make people whole. We do this not alone, but inspired and strengthened by Jesus Christ, His Father, and the Holy Spirit.

Judith Scott is an Axia board member and holds a master's in theology from Union Theological Seminary.