A class of eager-eyed Bible college students confidently entered the nave of the Greek Orthodox cathedral. I lagged behind the group, looking at the religious paintings in the narthex, eyeing a pile of candles beside what looked like a small elevated sandbox. Some stubby, unlit candles stuck up out of the sand.

We were greeted by a man in a long black robe, sporting wire-rimmed glasses and a trim beard. He welcomed us to take a seat. The rows of pews and stained glass windows were not unusual in a Christian church. But where I would have expected an altar was an ornamental wall with a number of doors and an image of Christ on one side and Mary with the Christ child on the other.

I was a first-year Bible college student and one of our required courses was World Missions. I wasn't particularly fond of the class. We had taken a number of field trips: to a mosque, to a synagogue, and now to this Greek Orthodox Church. I'd been both curious and embarrassed on our previous trips. The imam and the rabbi had been kind and patient with our self-assured group, despite the students’ presumptuous questions. This final trip seemed even more questionable to me, ostensibly “Greek Orthodoxy” was already Christian.

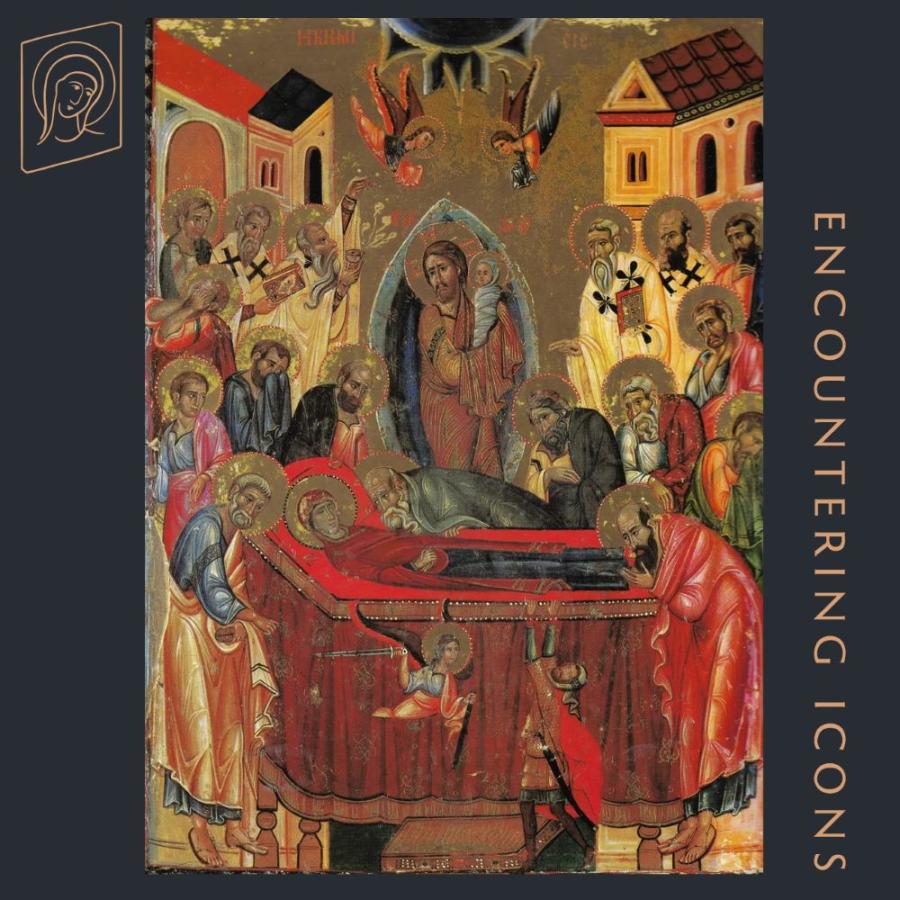

I looked around the nave of the cathedral as the man in the robe, who now introduced himself as a deacon, began speaking. The walls of the church held large frescoes: the crucifixion, the resurrection, the birth of Christ, a scene of Pentecost. One image showed Christ on a mountain flanked by two old men with a number of younger men flung at his feet. Although the language of iconography was entirely unknown to me–religious art was not part of my anabaptist upbringing–it wasn't difficult to identify the scriptural scenes in these frescoes. There was, however, one mysterious image I could not identify. A lady was lying on a bed surrounded by a group of onlookers, while Christ was leaning over her, inexplicably holding a small baby in his arms. My mind unsuccessfully cast around for an explanation.

Our host began describing various Orthodox practices, including the veneration of icons. Predictably, a student asked why the Orthodox worshiped idols. The deacon replied, “We venerate, not worship, icons. We venerate because we love Christ and His saints. It's not terribly unlike carrying a photo of your sweetheart in your wallet and when you are far away from each other, taking the photo out and kissing it." While I had never been seized with the desire to kiss a photo, this didn't seem like a wildly unchristian explanation.

Another student raised his hand, "Will you be in heaven?” I cringed. The deacon cheerfully replied, "I certainly hope so, but that is for God to judge. Will you be in heaven?”

I looked back at the mysterious fresco of the lady on the bed. Could the inclusion of this one image be enough to make Orthodoxy so non-Christian that it needed to be evangelized?

I do not recall anything more about that first encounter with icons or Orthodoxy. I left the Bible college at the end of the year and transferred to a Catholic university. At some point not long after that, I came across a book of icons in the library. Flipping through the images, I spied the icon of the Dormition of the Theotokos. A small jolt of recognition surged through me: it was the same–or clearly very close to the same–image I'd seen in the Greek church. But here there was an explanation: the woman on the bed was Mary and the child Christ carried was also somehow Mary–or an image of her soul being received by Christ into paradise. The Son cradling His mother, inverse of the familiar image of Mary cradling the infant Jesus. I found this bizarre and fascinating and beautiful.

Can I say that the icon of the Dormition led me to become Orthodox? Truthfully, I haven’t considered the possibility until now. What I would have said is that same year I met a young couple who had recently been chrismated Orthodox. They invited me to Vespers services, and to Pascha, and over to their apartment for many long dinners. And over time I became familiar with the ways Orthodox people venerated icons, and loved the saints, and lived their faith through participation in the Liturgy. After the unembodied pragmatism of Protestantism, it was a joy to worship God with all my senses, in spaces profuse with color and image.

In time, I too was chrismated. And yet I didn’t go and buy an icon of Dormition and hang it on my wall. Instead, the icon of the Dormition–not unlike the Theotokos herself– remained a quiet reminder of the way Orthodoxy opens up like a nesting doll, containing within itself innumerable mysteries. As an invitation to participate over and over again in all the fullness of our life in Christ. As the first step in a long journey, and as the last step in that same journey–hopefully, as the deacon said–into paradise.