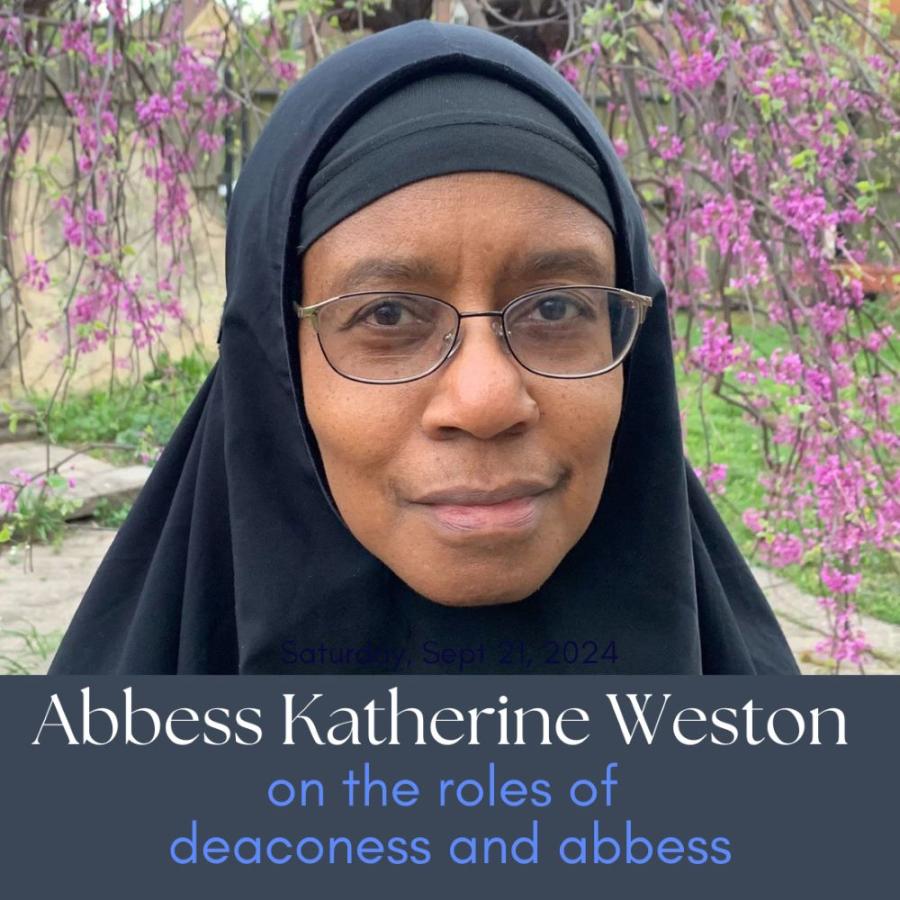

We are glad to be able to share with you, by permission, a reflection by Abbess Katherine Weston–superior of the St. Xenia Monastic Community for over 30 years and the President of the Fellowship of St. Moses the Black–in which she considers the role of deaconesses and abbesses.

Today, because of the recent and conspicuous ordination of a female deacon in Zimbabwe, I want to start to say something about ordination.

In our hyper-individualistic age, the most important thing to remember is the people are elevated to meet a need of the Church. I know a man who approached a bishop because he wanted the experience of serving the Liturgy, but not the responsibility of serving wherever the bishop might want to send him. He was turned down. Obviously Met. Seraphim of Zimbabwe felt the need for this new deacon’s service to the Church. His action has been praised by the St. Phoebe Center for the Deaconess as cracking the door open for other women. On the other hand, his action has been criticized by theologian Jeanie Constantinou as not being conciliar. In her thinking, conciliar action is the bedrock of Orthodoxy, and unilateral actions lead to schism and division in the body of Christ.

While the Holy Spirit is sorting these matters out, let us pray for wisdom for Church leaders! In the meantime, regarding the female diaconate—it never fully died out. But because of the changing needs of the Church, it was absorbed into women’s monasticism. In some communities it is possible today to see nuns assisting in the altar. An abbess may hear the confessions of her nuns and then bring these collectively to the pastor for absolution. In time of need, she may even distribute the Holy Gifts to her flock.

Earlier, I said that “regarding the female diaconate—it never fully died out. But because of the changing needs of the Church, it was absorbed into women’s monasticism.” So picking up that thread, let’s say more about the abbess. I will begin with honors, not so that anyone should think more highly of me, but to impress upon you the honor which the Church already confers on the female sex.

An abbess is chosen from the vowed monastic sisterhood. We say that monastics are “tonsured,” priests are “ordained,” bishops are “consecrated.” The abbess is “elevated” by her bishop. The rite that is used to elevate an abbess is the exact same one used to elevate an archimandrite. (This honor may be given to abbots, priestmonks, and celibate clergy.) The main difference in the rite (other than pronouns) is where the newly elevated one is placed afterwards. The archimandrite is instructed to sit with the other clergy, while the abbess may have a throne next to the bishop’s throne, to his left (that is, between the bishop and the congregation).

What does this signify? That she now has direct access to the bishop without any intermediary. The bishop also confers on her the authority to give blessings, just as he gives it to priests. Assuming that clergy are aware, the abbess and priest may greet one another the same way two priests greet each other, kissing each other’s hand. Some of the renowned abbesses have been awarded multiple pectoral crosses, just like renowned priests.

In her home monastery, the priest serves with her blessing. As I said last week, in some communities she receives the confessions of her sisterhood and presents them to the pastor for absolution. And in time of need, with her bishop’s blessing, she may distribute the Holy Gifts to the sisters. But honor is a token of responsibility. The abbess is entrusted with the care of souls and must answer for them. She must not be a hireling, but a shepherdess who will lay down her life for her flock. The initial instructions she receives are sobering, and no one would wish to take up that cross without being called.

So let us compare the deaconess in the early church with today’s abbess. The deaconess was unmarried or widowed and had to be of mature years (60, then 40 years old). The abbess, like all monastics, is celibate and should be wise, although there is no age restriction. The deaconess was set aside for ministry to other women, going into their homes and assisting in baptisms so that the priest would not see women undressed.

The abbess is set aside for ministry to women, in her own community, for pilgrims, and in her travels. The deaconess could bring the Eucharistic Gifts to women in their homes. As we said above, the abbess can, with her bishop’s blessing, give them to her sisters. The deaconess, we believe, was ordained in the altar during the Divine Liturgy. The abbess is elevated outside of the altar and outside of the Liturgy. But paradoxically, the deaconess was responsible to her priest, while the abbess is responsible to her bishop.

I hope that by this description and comparison, you now understand why I say that the function of the early deaconess has been largely absorbed by the role of the abbess.

Lord, we thank you for the honors and responsibilities which You have given to women through the monastic orders. As you once freed the Paralytic from sin and despair, free us from the mind of this world and help us to seek You and Your will at all times. Help us all to find moments of quiet prayer where we can grow closer to you. Amen.